Afghanistan's drug kingpins above the law

SFGate

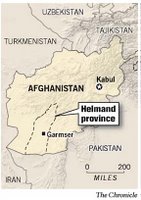

Garmser, Afghanistan -- The smugglers' trail jolts toward the southern border, crossing salt-encrusted plains, scrabbly farmland and hundreds of blossoming poppy fields. Suddenly, a fortress-like compound looms.

border, crossing salt-encrusted plains, scrabbly farmland and hundreds of blossoming poppy fields. Suddenly, a fortress-like compound looms.

Locals say the imposing, high-walled mansion near Garmser belongs to Haji Adam, a well-known drug smuggler. Tales of his wealth are legion. "When he became sick, he was flown directly to Germany," said a man in the village of Garmser, who asked not to be named. "Even helicopters have landed at his house," said another.

Like nearly every other major drug figure in the region, Adam appears to worry little about the law. "Many smugglers don't even bother hiding their wealth," said a British diplomat in Kabul, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "It's their way of saying 'screw you' to authority."

Another bumper drug harvest is expected in Afghanistan, and kingpins who control the $2.7 billion trade appear as untouchable as ever. Afghan poppy-eradication workers for DynCorp International, a Texas company that got a $174 million-a-year contract from the U.S. State Department's Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, are chopping down poppy crops. But targeting unarmed and penniless poppy farmers is easy; rounding up those at the pinnacle of the drug trade business is much harder.

Another bumper drug harvest is expected in Afghanistan, and kingpins who control the $2.7 billion trade appear as untouchable as ever. Afghan poppy-eradication workers for DynCorp International, a Texas company that got a $174 million-a-year contract from the U.S. State Department's Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, are chopping down poppy crops. But targeting unarmed and penniless poppy farmers is easy; rounding up those at the pinnacle of the drug trade business is much harder.

Afghanistan's top drug smugglers have been spectacularly successful at evading Western and Afghan law enforcement. Although Western drugs experts estimate there are several dozen major traffickers, just two have been arrested since the Western-funded war on drugs started four years ago -- Haji Baz Muhammad, who was extradited to the United States in October, and Bashir Noorzai, arrested on arrival in New York last April.

Several anti-drug experts working with Western embassies in Kabul, who spoke on condition of anonymity, gave The Chronicle a profile of the typical drug lord. Many live in fortified mansions, some defended with anti-aircraft guns. Loyal tribesmen and heavily armed private militias provide protection. And they reportedly enjoy political support at the highest levels of government.

Persistent allegations of drug links have dogged some of Afghanistan's most powerful figures, including several provincial governors, Cabinet ministers and the president's own brother, Walid Karzai. At least 17 members of the newly elected parliament have active links to the trade, according to a study by analyst Andrew Wilder of the Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit, a Kabul think tank.

But the most serious charges hover over Gen. Muhammad Daud, the deputy interior minister for counternarcotics. One senior drug official said his office was 99 percent sure that Daud was a player in the trade he is supposed to be destroying. The official spoke on condition that neither he nor his nationality be identified due to the extreme sensitivity of the subject. "He frustrates counternarcotics law enforcement when it suits him," the official said. "He moves competent officials from their jobs, locks cases up and generally ensures that nobody he is associated with will get arrested for drug crimes."

Daud denies the allegations. "These rumors are the work of my enemies," he said last year. At a news conference in February, he said his forces had confiscated more than 100 tons of drugs in 2005.

Afghan undercover drug teams have had limited success in penetrating the upper echelons of the drug networks. "Like most criminal masterminds, they don't get their hands dirty with actual gear. You try to get to their lieutenants, use intelligence to see what they're up to and find where the money goes," said the official.

Typically, he said, drug kingpins have established power bases from their days as mujahedeen commanders or tribal elders. They slip easily in and out of Afghanistan using false passports or, less often, small aircraft that can evade U.S. air traffic controllers based in Qatar.

Many strike deals during the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia. "The hajj is a good place to do business, we believe," the official said.

Western drug experts say part of the illicit profits are invested in Kabul, where new glass-fronted commercial buildings and gaudy mansions are springing up. Much of the rest may end up in Dubai, where Western intelligence agents are working with officials of United Arab Emirates to stanch the flow of drug money, the experts said.

Fears that Afghanistan is becoming a full-fledged "narco-state" are swelling fast. Poppy cultivation dipped by 21 percent in 2005, after President Hamid Karzai declared a jihad -- a government-sanctioned holy war on drugs -- but is expected to rise sharply this year, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime. The greatest spike, as much as 100 percent, is expected in Helmand province, where Adam, the well-known smuggler, lives.

The desolate, sun-baked plains of southern Helmand are one of the world's busiest heroin smuggling hubs. At night, high-speed convoys race across the hard-packed desert toward Pakistan. The border, which is controlled by Baluch tribesmen, has little relevance. "It's basically Baluchistan, with a line running through it that happens to have been drawn by some white guys," said the senior drug official.

The main smuggling hub is Baramcha, a notoriously lawless village on the plains. It is entirely unpatrolled -- the last border police fled for their lives five months ago, said Allahuddin, the district intelligence chief, who goes by one name. "They attacked the customs post, killed our soldiers and cut off their heads," he said.

From Baramcha, bricks of opium derived from the poppy sap are spirited away by jeep, camel or bus, either south toward Pakistan's Makran Coast or west into Iran. After it is purified into heroin, most ends up on the streets of Europe.

Instability in the border area is fueled by a recent pact between Taliban fighters and drug smugglers, apparently rooted in their shared interest in excluding Karzai's pro-U.S. government from the area. Last December, the Taliban attacked Garmser police headquarters, killing nine officers. Smugglers provided the vehicles, said district Gov. Haji Abdullah Jan. "Now they are working together," he said.

British forces arriving in Helmand as part of a NATO mission will soon mount patrols along the porous border, said Lt. Col. Henry Worsley, a British commander in the provincial capital, Laskhar Gah.

In Kabul, the dilapidated justice system is being overhauled to help prosecute drug lords. A new counternarcotics law was recently approved, and a special drug court has been set up in Kabul. So far, 14 judges, 36 investigators and 32 prosecutors have received training. The court already has heard several hundred cases, mostly involving low-level couriers and laboratory operators.

But even when drug criminals are prosecuted, they frequently bribe their way to freedom, Western officials say. As a result, the United States is now helping finance construction of a new drug lock-up with a capacity for 50 prisoners at Policharki prison outside Kabul, due to open later this year. Government officials and Western diplomats say they hope to arrest the first major smuggler soon.

"I think if we get our act together, it's not unrealistic," said the British diplomat. "But around here nothing is for sure."

By Declan Walsh

Garmser, Afghanistan -- The smugglers' trail jolts toward the southern

border, crossing salt-encrusted plains, scrabbly farmland and hundreds of blossoming poppy fields. Suddenly, a fortress-like compound looms.

border, crossing salt-encrusted plains, scrabbly farmland and hundreds of blossoming poppy fields. Suddenly, a fortress-like compound looms.Locals say the imposing, high-walled mansion near Garmser belongs to Haji Adam, a well-known drug smuggler. Tales of his wealth are legion. "When he became sick, he was flown directly to Germany," said a man in the village of Garmser, who asked not to be named. "Even helicopters have landed at his house," said another.

Like nearly every other major drug figure in the region, Adam appears to worry little about the law. "Many smugglers don't even bother hiding their wealth," said a British diplomat in Kabul, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "It's their way of saying 'screw you' to authority."

Another bumper drug harvest is expected in Afghanistan, and kingpins who control the $2.7 billion trade appear as untouchable as ever. Afghan poppy-eradication workers for DynCorp International, a Texas company that got a $174 million-a-year contract from the U.S. State Department's Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, are chopping down poppy crops. But targeting unarmed and penniless poppy farmers is easy; rounding up those at the pinnacle of the drug trade business is much harder.

Another bumper drug harvest is expected in Afghanistan, and kingpins who control the $2.7 billion trade appear as untouchable as ever. Afghan poppy-eradication workers for DynCorp International, a Texas company that got a $174 million-a-year contract from the U.S. State Department's Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, are chopping down poppy crops. But targeting unarmed and penniless poppy farmers is easy; rounding up those at the pinnacle of the drug trade business is much harder.Afghanistan's top drug smugglers have been spectacularly successful at evading Western and Afghan law enforcement. Although Western drugs experts estimate there are several dozen major traffickers, just two have been arrested since the Western-funded war on drugs started four years ago -- Haji Baz Muhammad, who was extradited to the United States in October, and Bashir Noorzai, arrested on arrival in New York last April.

Several anti-drug experts working with Western embassies in Kabul, who spoke on condition of anonymity, gave The Chronicle a profile of the typical drug lord. Many live in fortified mansions, some defended with anti-aircraft guns. Loyal tribesmen and heavily armed private militias provide protection. And they reportedly enjoy political support at the highest levels of government.

Persistent allegations of drug links have dogged some of Afghanistan's most powerful figures, including several provincial governors, Cabinet ministers and the president's own brother, Walid Karzai. At least 17 members of the newly elected parliament have active links to the trade, according to a study by analyst Andrew Wilder of the Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit, a Kabul think tank.

But the most serious charges hover over Gen. Muhammad Daud, the deputy interior minister for counternarcotics. One senior drug official said his office was 99 percent sure that Daud was a player in the trade he is supposed to be destroying. The official spoke on condition that neither he nor his nationality be identified due to the extreme sensitivity of the subject. "He frustrates counternarcotics law enforcement when it suits him," the official said. "He moves competent officials from their jobs, locks cases up and generally ensures that nobody he is associated with will get arrested for drug crimes."

Daud denies the allegations. "These rumors are the work of my enemies," he said last year. At a news conference in February, he said his forces had confiscated more than 100 tons of drugs in 2005.

Afghan undercover drug teams have had limited success in penetrating the upper echelons of the drug networks. "Like most criminal masterminds, they don't get their hands dirty with actual gear. You try to get to their lieutenants, use intelligence to see what they're up to and find where the money goes," said the official.

Typically, he said, drug kingpins have established power bases from their days as mujahedeen commanders or tribal elders. They slip easily in and out of Afghanistan using false passports or, less often, small aircraft that can evade U.S. air traffic controllers based in Qatar.

Many strike deals during the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia. "The hajj is a good place to do business, we believe," the official said.

Western drug experts say part of the illicit profits are invested in Kabul, where new glass-fronted commercial buildings and gaudy mansions are springing up. Much of the rest may end up in Dubai, where Western intelligence agents are working with officials of United Arab Emirates to stanch the flow of drug money, the experts said.

Fears that Afghanistan is becoming a full-fledged "narco-state" are swelling fast. Poppy cultivation dipped by 21 percent in 2005, after President Hamid Karzai declared a jihad -- a government-sanctioned holy war on drugs -- but is expected to rise sharply this year, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime. The greatest spike, as much as 100 percent, is expected in Helmand province, where Adam, the well-known smuggler, lives.

The desolate, sun-baked plains of southern Helmand are one of the world's busiest heroin smuggling hubs. At night, high-speed convoys race across the hard-packed desert toward Pakistan. The border, which is controlled by Baluch tribesmen, has little relevance. "It's basically Baluchistan, with a line running through it that happens to have been drawn by some white guys," said the senior drug official.

The main smuggling hub is Baramcha, a notoriously lawless village on the plains. It is entirely unpatrolled -- the last border police fled for their lives five months ago, said Allahuddin, the district intelligence chief, who goes by one name. "They attacked the customs post, killed our soldiers and cut off their heads," he said.

From Baramcha, bricks of opium derived from the poppy sap are spirited away by jeep, camel or bus, either south toward Pakistan's Makran Coast or west into Iran. After it is purified into heroin, most ends up on the streets of Europe.

Instability in the border area is fueled by a recent pact between Taliban fighters and drug smugglers, apparently rooted in their shared interest in excluding Karzai's pro-U.S. government from the area. Last December, the Taliban attacked Garmser police headquarters, killing nine officers. Smugglers provided the vehicles, said district Gov. Haji Abdullah Jan. "Now they are working together," he said.

British forces arriving in Helmand as part of a NATO mission will soon mount patrols along the porous border, said Lt. Col. Henry Worsley, a British commander in the provincial capital, Laskhar Gah.

In Kabul, the dilapidated justice system is being overhauled to help prosecute drug lords. A new counternarcotics law was recently approved, and a special drug court has been set up in Kabul. So far, 14 judges, 36 investigators and 32 prosecutors have received training. The court already has heard several hundred cases, mostly involving low-level couriers and laboratory operators.

But even when drug criminals are prosecuted, they frequently bribe their way to freedom, Western officials say. As a result, the United States is now helping finance construction of a new drug lock-up with a capacity for 50 prisoners at Policharki prison outside Kabul, due to open later this year. Government officials and Western diplomats say they hope to arrest the first major smuggler soon.

"I think if we get our act together, it's not unrealistic," said the British diplomat. "But around here nothing is for sure."

By Declan Walsh

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home